Lisson Studio

Ding Yi

Ding Yi in Yunnan: The Road to Heaven

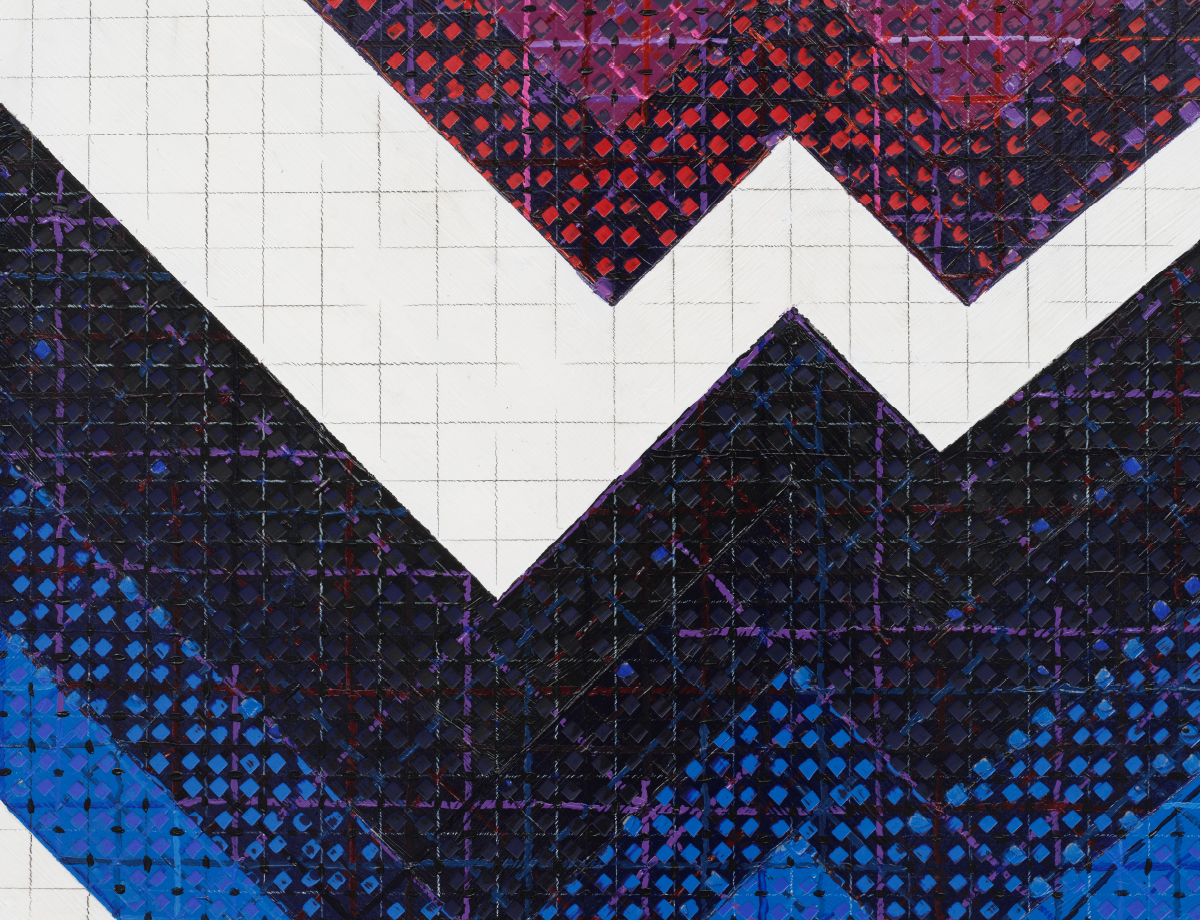

For his inaugural solo exhibition at Lisson Gallery and his first return to exhibit in London in over five years, renowned Chinese abstractionist Ding Yi presents The Road to Heaven a new body of work ahead of Frieze week. This latest series is deeply informed by the history and cosmology of the Naxi people of Yunnan in southwestern China, offering a rich cultural and conceptual dimension to his distinctive visual language. In line with his larger corpus, the artist’s latest drawings and paintings employ a systematic iconography in the service of a layered, subjective response – a continuous act of translation rather than a fixed text.

The Road to Heaven documentary by Pema Tashi follows Ding Yi’s journey through Yunnan in black and white, before blooming into full colour as it explores his artworks.

As Curatorial Director Greg Hilty writes in the catalogue Ding Yi: The Winding Path: "Yunnan is famous for being home to Dongba culture, representing the spirit and history of the Naxi people. Dongba culture is named after the Dongba, priests or ritualists (always men) who were and remain keepers and interpreters of the sacred texts, written in the form of pictorial glyphs. The Naxi are now highlighted as one of the acknowledged ethnic minorities respected within the PRC. Dongba culture is carefully preserved and studied, providing the basis (along with spectacular landscape and appealing climate) for significant internal tourism."

© The Road to Heaven, documentary, director: Pema Tashi, 2025

"While researching carefully and speaking directly to many practitioners, Ding Yi engaged with the culture creatively rather than appropriating or illustrating it, using his own simple and inclusive structural framework to iterate new thoughts inspired by it. He makes no claims of course for the authenticity or ritual use of his interpretations. Instead, he respectfully but creatively brings references to historic Dongba traditions into the ritual system of the contemporary art world. The porous, self-conscious, and ambiguous nature of those traditions, alongside the compelling world views they represented and the profound meanings they held for their practitioners and audiences, lend depth to their re-iteration within Ding Yi's resilient methodology.

In their heyday, the Dongba were the most influential people in their societies, with links to powerful families and other authorities within the culture. When someone had a problem they would come to the Dongba, who also had rights over the symbolism and imagery of the local culture. I asked Ding Yi how he saw his own role in relation to this. He said: "in the traditional society, when people didn't know what to do, they would turn to the ritualist. Now, they look to the artist, but in a different way. The artist opens up new vistas and paths without telling the viewer to go down them, or where they will lead."

"Ding Yi, a key leader of the comparable generation of founding figures of Chinese contemporary art, famously chose an abstract symbol as the basis of his work from 1988, at a time when nearly all his contemporaries were practising varied forms of representation. His ‘cross' icon, either in the form of an ‘A' or ‘B', was drawn not from mathematics but as a by-product of the industrial printing process, a throwaway sign of popular culture. For the best part of the first decade of his career, Ding Yi explored how variously he could express this simple device, arrayed in strict vertical and horizontal formats. Soon enough, his obsessive experiments in formalism brought him back to the world. First, in the apparently simple but resonant use of readymade tartan (replacing bare linen) as his ground. This provided a layer of cultural reference to his ongoing and evermore ambitious formal explorations. Second, by broadening the colour palette and the structure of his mark making – while still employing the core ‘cross' device as his only ostensible subject matter – Ding Yi expanded his language, introducing coded references to the world around him into his still abstract practice. The introduction of dynamic, radiating geometries, rendered often in shocking fluorescent colours, made clear reference to the dizzying expansion of the built environment in his hometown of Shanghai and China more widely, during the late 1990s and early 2000s."